Recent clashes between the police and protesters in Georgia, brought on by a controversial “foreign agent” law, have highlighted a major divide between the authorities and the wider population.

On Tuesday and Wednesday nights, thousands of Georgians took to the streets of the capital, Tbilisi, protesting against parliament’s backing of the first reading of the proposed law which critics say will limit press freedom and be used to crack down on non-governmental and other rights organisations.

Riot police used water cannon and pepper spray to disperse protesters in front of the parliament building, with some in the crowd shouting “down with the Russian law” – a reference to the fact that the proposed bill mirrors similar legislation in Moscow.

But this issue is only the latest indication of a wider struggle over the future direction of the country between pro-Western and pro-Russian views.

The political rift between the government and the public was already apparent when the Georgian government refused to take sides in the war in Ukraine – despite many Georgians sympathising with Ukraine, with some even going to fight against the Russian army.

What is the ‘foreign agent’ law?

If passed, the law will force all NGOs and media who receive more than 20% of their funding from abroad to be included in a special register and submit an annual financial declaration. Failure to submit such declaration will be punished with a $9,500 (£8,000) fine.

The Georgian Justice Ministry has said that this move would help to expose “agents of foreign influence” in the country. Supporters of the law argue that the US has similar legislation – the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA).

Opponents of the law condemn it as an attempt to mimic Russia’s own crackdown on freedom of speech and a sign that Moscow’s influence was growing. Crucially, they see the law as a major barrier to Georgia’s chances of joining the EU.

The country’s current ruling party, Georgia Dream, has had a majority in parliament for more than a decade now. While in theory the party supports orientating towards the EU and its values, it is also friendly with Russia.

Many would say this is a stance born out of pragmatism, made necessary by the country’s recent history.

Traumas from the past

Georgia became independent in 1991 following the breakup of the Soviet Union but experienced a period of internal instability for much of the next decade, during which the region of Abkhazia proclaimed its own independence.

Tbilisi has said that the breakaway region was occupied by Russia and has remained occupied ever since.

In the 2000s and 2010s, Georgia opened up its economy to foreign investment and tried to clean up corruption and move closer to the EU and Nato.

In 2008, after a five-day war, Russian troops occupied another Georgian region – South Ossetia – a small mountainous area to the north-west of Tbilisi.

The region later proclaimed its independence too, which is recognised by a handful of countries, including Russia itself, as well as Syria and Venezuela. South Ossetia is still effectively under Russian occupation.

Most Georgians are wary of further conflict, and according to opinion polls, most would like to see the issue of South Ossetia and Abkhazia resolved peacefully.

Ukraine war and internal divisions

At the same time, the government’s refusal to openly back Ukraine or impose sanctions after Russia’s full-scale invasion last February has angered many Georgians, who see this conflict as Moscow’s war of aggression.

This neutrality is emphasised by the giant illuminated display reading “Tbilisi – a city of peace” that the authorities have put up – but it stands in contrast to the fact that many Georgians have volunteered to fight in a foreign unit alongside Ukrainian forces against the Russian army.

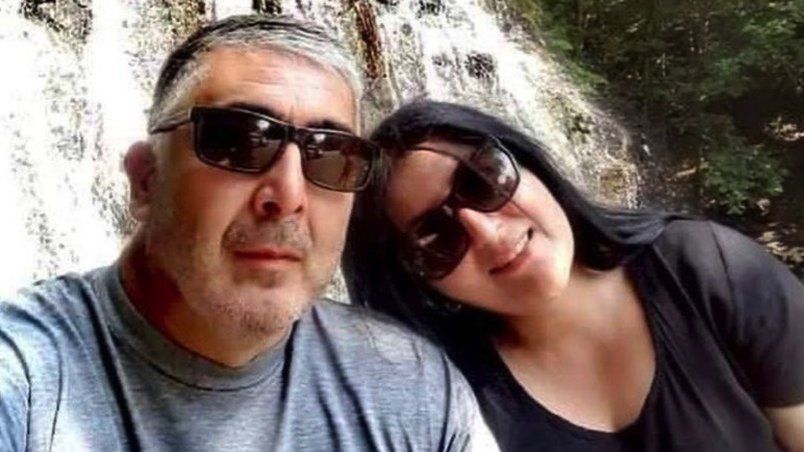

One such fighter was David Ratiani, a former military officer who had fought in Abkhazia and later served in the Georgian contingent of the Nato-led mission in Afghanistan.

When the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine started, the 52-year-old father of three went to Ukraine and was later killed – one of dozens of Georgians to have died.

The exact number of Georgians fighting in Ukraine is unknown but it is thought to be at least in the hundreds.

David Ratiani’s widow, Iya, has said her husband was convinced joining Ukraine’s cause was the right thing to do.

“He told me he was doing it for our children, so that they wouldn’t have to pick up arms when they are older and so that they can live in a better country. He said that our country will be better if Ukraine wins in this war and he has to help Ukraine.”

Georgian authorities have tried to stop volunteers from Georgia leaving for Ukraine, saying that this would directly draw the country into the conflict. In the end, many have still managed to get to Ukraine but the government had distanced itself from them.

Iya has said her last conversation with her husband was on 16 March last year. They were able to talk over a video link. She even tried on a new dress and her husband complimented her on how well the colour red suited her.

She could see that he was preoccupied and stressed. He told her how shocked he was to walk into a Ukrainian home that recently been abandoned by people who’d had to leave everything behind to flee the fighting.

“He said ‘this is Georgian history repeating itself in Ukraine’ – referring to the Georgians fighting the Russian forces in Abkhazia in the 1990s,” Iya remembers.

War and peace

On the first anniversary of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Georgian government called for calm and insisted that its position was motivated by a desire to “preserve peace”. It also voiced concerns that there are those who want to bring the conflict into Georgia.

Georgian Prime Minister, Irakli Garibashvili, has said that his government has prevented Georgia being turned “into another theatre of war.”

“Had there been a more destructive force in power, by now a large part of Georgia, just like Ukraine, would have been turned into a combat zone,” he said.

“Let us live peacefully and let us each take care of our own country.”

But the opposition, joined by hundreds of its supporters, still took to the streets to mark the anniversary in support of Ukraine and to commemorate those who had been killed, including Georgian fighters.

Source: BBC