In a dramatic development, the leaders of Armenia and Azerbaijan issued a surprise joint statement on 7 December, outlining a prisoner exchange and mutual confidence-building measures, while committing to continue negotiations on normalizing relations and reaching a long-elusive peace treaty.

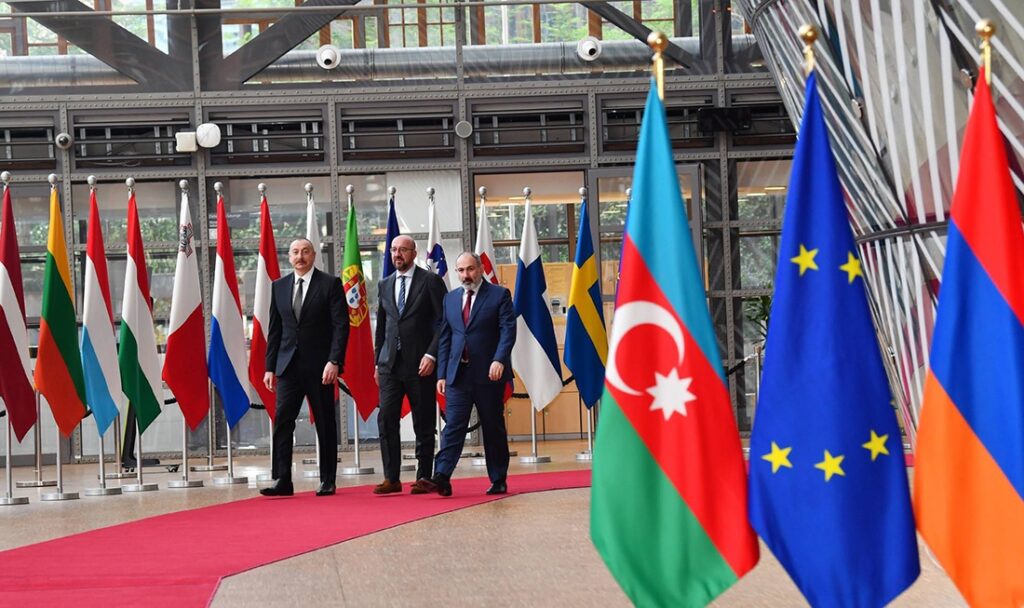

The joint statement by the offices of the Armenian Prime Minister and Azerbaijani President opens the path to a full-fledged peace treaty, as European and American diplomats have indicated.

Most notably, “for humanitarian reasons” and as a “gesture of goodwill,” Azerbaijan agreed to release 32 Armenian military personnel, while Armenia will free two Azerbaijanis. This will be the first mass prisoner-of-war exchange in years, especially on terms so favorable to Armenia.

The countries also concurred on reciprocal symbolic gestures. Yerevan will withdraw its bid to host the next UN Climate Change Conference (COP29) in favor of Baku, and even calls on other Eastern European states to back Azerbaijan’s application. In return, Baku endorses Armenia’s candidacy for membership in the COP Eastern European States Bureau.

This agreement was a sensation, as just days prior there was no indication of such a breakthrough in relations. On the contrary, there were good reasons to expect a sharp deterioration of relations and intensified fighting on the Armenian-Azerbaijani border. The “one-day war” of 19 September that allowed Baku to regain control of Nagorno-Karabakh had nearly buried peace talks between the countries, according to European Pravda editor Yuriy Panchenko.

For years since the war in Nagorno-Karabakh, a region with a predominantly ethnic Armenian population but located within Azerbaijan, ended in a precarious ceasefire in 1994, negotiations occurred simultaneously in two formats: Western and Russian.

The Western dialogue was important for Baku since Yerevan, which gained control of Nagorno- Karabakh, had to recognize Azerbaijan’s territorial integrity. It was also important for Yerevan as security guarantees for Karabakh Armenians were discussed.

Russia, meanwhile, proposed postponing Karabakh status issues (ideal for Armenia but unacceptable to Azerbaijan) while raising the issue of a transport corridor through Armenia (favorable to Baku but completely unacceptable to Yerevan).

Regaining Karabakh completely changed these dynamics.

Now, the Russian track lost all value for Yerevan – one reason for the current freeze in Armenia-Russia relations. Meanwhile, Azerbaijan lost interest in Western mediation, especially amidst accusations of “ethnic cleansing in Karabakh.” As a result, Baku’s statements became increasingly aggressive, raising the likelihood of a new regional conflict.

So why did Baku pivot from bellicose rhetoric towards conciliation? American pressure seems the impetus. Recent weeks saw multiple forceful warnings from Washington about the unacceptability of coercion toward Armenia. Significantly, US State Department sanctions coordinator Jim O’Brien visited Baku the very day this statement emerged, later tweeting about resumed Armenia-Azerbaijan peace talks.

The text itself also spotlights “discussions regarding the implementation of more confidence building measures.” Both sides call for international backing to build “mutual trust” and “positively impact the entire South Caucasus region.”

This likely constitutes the key passage, with adversaries confirming readiness to restart dialogue. The immediate result is drastically reduced regional war risks.

But the omission of Moscow from this significant process, despite decades of Russian mediation attempts, constitutes the developments’ sharpest rebuke for the Kremlin. Perhaps consequently, initial official Russian reactions to the agreed statement proved remarkably restrained and understated, with Foreign Ministry representative Maria Zakharova offering routine approval of progress while insisting upon Russia’s past useless “assistance” contributions regarding negotiations.

“We are ready to continue providing all possible assistance in unblocking transport communications, border delimitation, conclusion of a peace treaty, and contacts along the line of civil society,” she claimed.

However, Russia’s mediation appears no longer necessary – further peace talks will occur under EU and US auspices. A signed peace agreement will end Russia’s South Caucasus influence.

Theoretically, the Kremlin can still sabotage talks, given its military presence in both countries. But without political backing in either Armenia or Azerbaijan this is clearly insufficient to change the course of the countries, Panchenko stresses.

“So, if the West is persistent, signing a peace agreement in the coming months-by the middle of next year-is a very realistic scenario, snd this will be a foreign policy disaster for Russia. Hopefully, not the last,” Panchenko sums up.

Source : Euromaidan